Lumbar Vertebrae

Updated:

Relevant Bony Anatomy

The lumbar vertebrae (of the lower back) are the largest vertebrae within the spine. This is necessary to provide a strong foundation to support the weight of our head, arms and trunk.

There are five lumbar vertebrae (namely L1 to L5, from top to bottom). The L1 vertebra articulates (forms a joint) with the 12th thoracic vertebra, whilst the L5 vertebra articulates with the sacrum (tail bone). Occasionally, a 6th lumbar vertebra is present as part of the sacrum. This is termed ‘lumbarisation of S1’ and is present from birth in a relatively low percentage of the population.

Typical lumbar vertebrae primarily comprise of a heart shaped body (at the front of the bone) and a vertebral arch (situated directly behind the body), which forms a hole known as the vertebral foramen. Since each lumbar vertebrae is situated directly above or below each other, their collective vertebral foramen line up forming the vertebral canal which houses and protects the spinal cord. In the lumbar spine, the vertebral foramen is relatively larger than the thoracic spine (upper back) as it has to accommodate the lumbar and sacral plexus’ (all the nerves to supply the lower limbs).

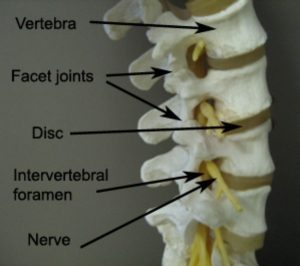

Each lumbar vertebra joins with adjacent lumbar vertebrae primarily at the facet joints (located at the back, and on each side, of the spine) and the discs of the lumbar spine (located centrally at the front of the spine) (figure 1). Movements between each adjacent vertebra are relatively small, but when summated over the entire vertebral column allow considerable mobility.

Figure 1 – Anatomy of the Lumbar Vertebrae

In the lumbar spine the facet joints are orientated in the sagittal plane, which means the primary movement of the lumbar spine is flexion/extension (i.e. forward and backward bending of the spine), allowing only limited rotation or side flexion (side bending).

Each lumbar vertebra also has various bony prominences, such as the spinous processes (located at the back of the bone) and transverse processes (located at each side of the vertebra). These bony prominences provide attachment points to the ligaments and muscles of the lumbar spine. In the lumbar spine, the spinous processes are short, broad and thick. They need to be broad to create a strong attachment point for muscles, whilst they need to be short and horizontally orientated, to allow extension (arching backwards). The L5 vertebra has a slightly smaller spinous process than the L1-L4 vertebrae, to allow it to articulate with the sacrum.

There are several other distinguishing features of lumbar vertebrae. Unlike thoracic vertebrae, the lumbar vertebrae do not articulate with the ribs. The lumbar vertebrae are also bigger. This is especially apparent when comparing the size of the vertebral bodies. The vertebral bodies in the lumbar spine are larger and more oval shaped. This is necessary as the lumbar spine supports more weight than the cervical (neck) and thoracic (upper back) spines. The vertebral bodies are also slightly wedge shaped (thicker at the front and narrower at the back) to give us the natural curve of our lower back, known as the lumbar lordosis.

A commonly injured part of the lower back are the lumbar discs. These are located between the vertebral bodies of each lumbar vertebra. The disc (also known as intervertebral disc) is in fact a joint – a fibrocartilaginous joint. Its main role is to provide strength and shock absorption, but also to allow flexibility of the vertebral column (spine). It does this through its unique design. The outer part (wall) of the disc is constructed of supportive fibrous rings, known as the annulus fibrosis. These rings are aligned as cross bridges for added strength and support. The inner part of the disc is made of a jelly-like viscous fluid, called the nucleus pulposis, which helps absorb shock and weight bearing forces. When doing this, the fluid spreads outwards to meet the opposing resistance of the annulus fibrosis. Injuries to the lumbar disc typically involve damage to the annulus fibrosis and subsequent bulging of the nucleus pulposis. This is known as a lumbar disc bulge.

Interestingly, the disc is the largest avascular structure in the body. This means that it has no direct blood supply. Instead its nutrition relies on blood flow diffusing through the tiny arteries (capillary beds) found in the intervertebral bodies above and below. In regards to nerve supply, only the outer third of the annulus fibrosis has a nerve supply.

Location

The five lumbar vertebrae are located at the bottom of the spine. The five lumbar vertebrae are numbered from the top to the bottom as L1 to L5.

Forms Joints With

- T12 (lowest thoracic vertebrae) – L1 forms joints with T12 via the facet joints and disc.

- Each of the lumbar vertebrae (L1 – L5) connects with the vertebrae above and below via the facet (zygapophyseal) joints and via the intervertebral discs located centrally between each spinal segment.

- The Sacrum – L5 also forms joints with the sacrum (at S1) via the facet joints and via an intervertebral disc. The iliolumbar ligaments assist in stabilizing this joint, attaching the L5 to the sacrum and ilium of the pelvis.

Major Muscles of the Lumbar Spine

Trunk Muscles

- Rectus Abdominis – running from the pubic bone (pubic symphysis and pubic crest) and inserting into the breast bone (xiphoid process) and 5th – 7th rib cartilages (costal cartilages), this muscle flexes the trunk and lumbar spine, as well as compresses the contents of the abdomen (abdominal viscera).

- External Oblique – running from the external surfaces of the 5th – 12th ribs and inserting into the midline of the abdomen (linea alba), pubic tubercle and anterior half of the iliac crest (parts of the pelvic bone), this muscle flexes and rotates the trunk and lumbar spine, as well as compresses and supports the abdominal viscera. The muscle fibres run obliquely downwards towards the midline (like placing your hands in your pocket).

- Internal Oblique – deep to external oblique, this muscle originates from the connective tissue of the back (thoracolumbar fascia), the anterior 2/3rd of the iliac crest (part of the pelvic bone) and lateral half of the inguinal ligament (at the front of the groin). The fibres run obliquely upwards towards the midline (opposite to external oblique), to insert into the inferior borders of the 10-12th ribs, the midline of the abdomen (linea alba) and pubis (via the conjoint tendon). Its action is similar to the external oblique, as it flexes and rotates the lumbar spine and trunk, as well as supporting the abdominal viscera.

- Transversus Abdominis – this is the deepest abdominal muscle. It takes its origin from the rib cartilages (costal cartilages) of the lower 6 ribs, the diaphragm, the connective tissue of the back (thoracolumbar fascia), the inner lip of the iliac crest (pelvic bone), the inguinal ligament (at the front of the groin) and the connective tissue (fascia) over the iliacus muscle (hip flexor). Its fibres run horizontally and laterally to insert into the pubic bone (pubic crest) and connective tissue (aponeurosis) of the internal oblique muscle. When it contracts, this muscle helps to compress the ribs and abdominal contents (viscera) by “drawing-in”. This increases intra-abdominal pressure – important for functions, such as defecation (going to the toilet), coughing and child-birth. Because of its attachments into the posterior lumbar spine, this “drawing-in” action assists in core stability, trunk stability and pelvic stability, by tightening the connective tissue (fascia) of the lumbar spine.

Posterior Abdominal Wall Muscles

- Psoas Major – originates from the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs of T12-L5 and inserts (along with the tendon of iliacus), into the lesser trochanter of the femur (thigh bone). Functioning with iliacus (collectively referred to as iliopsoas) it flexes the vertebral column, hip and trunk, and helps stabilize the hip joint.

- Psoas Minor – only found in approximately 60% of people, psoas minor assists in flexing the pelvis and lumbar region. Its origin is the vertebral body and disc of T12-L1 and its insertion is the iliopubic eminence on the pelvic rim.

- Quadratus Lumborum – this muscle extends and laterally flexes (side bends) the vertebral column (spine). It also fixes the 12th rib during inspiration. Its origin is the medial half of the inferior border of the 12th rib and tips of the lumbar transverse processes. It inserts into the iliolumbar ligament and internal lip of the iliac crest (pelvic bone).

Posterior Vertebral Muscles – Superficial layer:

- Latissimus Dorsi – this broad back muscle runs from the spinous processes of the lower thoracic vertebrae and lumbar spine, as well as the connective tissue (fascia) of the thoracolumbar region, the pelvis and lower ribs, to insert into the upper arm bone (humerus). Its primary action is to extend, adduct and internally rotate the upper arm. It also influences movements of the trunk.

Intermediate Layer:

- Lumbar Erector Spinae – the main extensor (backward bending) muscle of the lumbar spine, located on either side of the vertebral column. Responsible for keeping the spine erect and helping to control forward and backward bending of the spine (flexion and extension). When acting unilaterally (on only one side of the body) it assists with side bending and spinal rotation to the same side.

Deep Layer:

- Transversospinalis Muscles – these shorter, deep muscles help stabilize the spinal segments. In the lumbar spine they are individually known as multifidus and rotatores (or deep multifidus). Rotatores lies deeper than multifidus and crosses 1-2 vertebral motion segments. Multifidus extends further, crossing 3-4 motion segments. They are situated deep to the erector spinae muscle, and run obliquely. They originate from the transverse processes of inferior vertebrae and attach to spinous processes of superior vertebrae. Acting bilaterally (on both sides of the spine) these muscles produce segmental extension (backward bending of the spine) and stability. Acting unilaterally these muscles produce side flexion to the same side and rotation to the contralateral side (opposite side).

Deepest Layer:

- Crossing only one vertebral motion segment, lie the short segmental muscles interspinalis and intertransversii. Interspinalis runs vertically from the spinous process of one vertebrae to the spinous process of the adjoining vertebrae, it assists with stability and extension of the vertebral column. Similarly, intertransversarii runs vertically from one transverse process to the next, and assists with lateral flexion (side bending).

Other Attachments

- Each lumbar vertebrae connects with the spinal segment above and below via an intervertebral disc.

- Numerous strong ligaments reinforce connections between adjacent lumbar vertebrae, and discs, providing stability (see Ligaments of the Spine).

Related injuries

- Lumbar Disc Bulge

- Facet Joint Sprain

- Postural Syndrome

- Sciatica

- Spondylolysis

- Spondylolithesis

- Spinal Degeneration

- Spinal Canal Stenosis

Relevant Physiotherapy Exercises

Recommended Reading

- View our Lower Back Diagnosis Guide.

- View detailed information on improving your Posture.

- View detailed information on Postural Taping.

- View detailed information on Ergonomic Computer Setup.

- View detailed information on Mobile Phone Ergonomics.

- View detailed information on Choosing a School Bag.

- View detailed information on Safe Lifting.

Find a Physio

Find a physiotherapist in your local area who can diagnose and treat sports and spinal injuries and provide education on the anatomy of the lumbar spine and lumbar vertebrae.

Link to this Page

If you would like to link to this article on your website, simply copy the code below and add it to your page:

<a href="https://physioadvisor.com.au/health/anatomy/bones/lumbar-vertebrae”>Lumbar Vertebrae – PhysioAdvisor.com</a><br/>PhysioAdvisor provides detailed physiotherapy information on the human anatomy of the lumbar spine and lumbar vertebrae. Including location, joints, muscular attachments, relevant injuries and more...

Return to the top of Lumbar Vertebrae.