LCL Tear (Members Only)

Updated:

(Also known as a LCL Tear, LCL Injury, Torn LCL, Lateral Collateral Ligament Tear, LCL Sprain, Sprained LCL, Ruptured LCL)

What is a LCL tear?

A LCL tear is a relatively common sporting injury affecting the knee and is characterized by tearing of the Lateral Collateral Ligament of the knee (LCL).

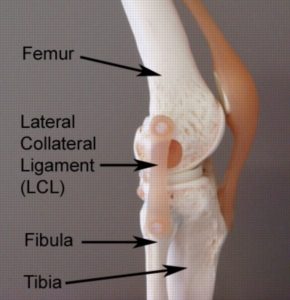

A ligament is a strong band of connective tissue which attaches bone to bone. The LCL is situated at the outer aspect of the knee joint and is responsible for joining the outer aspect of the femur (thigh bone) to the outer aspect of the fibula (outer lower leg bone) (figure 1).

The LCL is one of the most important ligaments of the knee, giving it stability. The LCL achieves this role by preventing excessive twisting, and side to side movements of the knee (varus forces – figure 2). When these movements are excessive and beyond what the ligament can withstand, tearing to the LCL occurs. This condition is known as a LCL tear.

A LCL tear may range from a small partial tear resulting in minimal pain, to a complete rupture of the LCL resulting in significant pain and disability. A LCL tear can be graded as follows:

- Grade 1 tear: a small number of fibres are torn resulting in some pain but allowing full function

- Grade 2 tear: a significant number of fibres are torn with moderate loss of function.

- Grade 3 tear: all fibres are ruptured resulting in knee instability and significant loss of function. Other structures may also be injured such as the menisci or cruciate ligaments.

Causes of a LCL tear

LCL tears typically occur during activities placing excessive strain on the LCL. This generally occurs suddenly due to a specific incident, however, occasionally may occur due to repetitive strain. There are two main movements that place stress on the LCL, these include:

- twisting of the knee

- varus forces on the knee (figure 2)

When these movements (or combination of these movements) are excessive and beyond what the LCL can withstand tearing of the ligament may occur.

LCL tears are frequently seen in contact sports or sports requiring rapid changes in direction. These may include: football, netball, basketball and downhill skiing. The usual mechanism of injury is a twisting movement when weight-bearing (especially when landing from a jump) or due to a collision to the inner knee, forcing the knee to bend in the wrong direction (such as another player falling across the inside of the knee). Occasionally a LCL tear may occur gradually due to repetitive activities placing strain on the ligament.

Signs and Symptoms of a LCL tear

Patients with this condition may notice an audible snap or tearing sound at the time of injury. In minor cases, patients may be able to continue activity only to experience an increase in pain, swelling and stiffness in the knee after activity with rest (particularly first thing in the morning). Often the pain associated with a torn LCL is localized to the outer aspect of the knee.

In cases of a complete rupture of the LCL, pain is usually severe at the time of injury, however, may sometimes quickly subside. Patients may also experience a feeling of the knee going out and then going back in as well as a rapid onset of swelling (within the first few hours following injury). Patients with a complete rupture of the LCL generally can not continue activity due to pain or the knee feeling unstable. Occasionally, the patient may be unable to weight bear at the time of injury due to pain and may develop bruising and knee stiffness over the coming days.

Diagnosis of a LCL tear

A thorough subjective and objective examination from a physiotherapist is usually sufficient to diagnose a LCL tear. Investigations such as an X-ray, MRI scan or CT scan may be required to confirm diagnosis and determine the extent of damage or involvement of other structures within the knee.

Treatment for a LCL tear

Most patients with this condition heal well with appropriate rehabilitation. The success rate of treatment is largely dictated by patient compliance. A vital aspect of treatment is that the patient rests sufficiently from any activity that increases their pain (a knee brace or the use of crutches are often required to ensure activity is pain free). Activities placing large amounts of stress on the LCL should also be minimized, particularly twisting, varus forces to the knee (figure 2) and excessive weight bearing activity such as prolonged standing or walking (especially up hills or on uneven surfaces), running, jumping, squatting, lifting or kneeling. Resting from aggravating activities ensures the body can begin the healing process in the absence of further tissue damage. Once the patient can perform these activities pain free a gradual return to these activities is indicated provided there is no increase in symptoms.

Ignoring symptoms or adopting a ‘no pain, no gain’ attitude is likely to lead to the condition becoming chronic. Immediate, appropriate treatment in patients with a torn LCL is essential to ensure a speedy recovery. Once the condition is chronic, healing slows significantly resulting in markedly increased recovery times, an increased likelihood of future recurrence and chronic knee instability.

Patients with this condition should follow the R.I.C.E. Regime in the initial phase of injury. The R.I.C.E regime is beneficial in the first 72 hours following a LCL tear or when inflammatory signs are present (i.e. morning pain or pain with rest). The R.I.C.E. regime involves resting from aggravating activities (this may include the use of a knee brace, knee taping or the use of crutches), regular icing (i.e. 20 minutes every 2 hours), the use of a compression bandage and keeping the leg elevated. Anti-inflammatory medication may also significantly hasten the healing process by reducing the pain and swelling associated with inflammation.

Manual “hands-on” therapy from the physiotherapist such as massage, trigger point releases, joint mobilisation, dry needling, stretches and electrotherapy can also assist with improving range of movement and function following a LCL tear. This can generally commence once the physiotherapist has indicated it is safe to do so.

Patients with a LCL tear should perform pain-free flexibility and strengthening exercises as part of their rehabilitation to ensure an optimal outcome. One of the key components of rehabilitation is pain-free strengthening of the quadriceps (vastus medialis obliquus muscle – VMO), hamstring, gluteal and calf muscles to improve the control of the knee joint with weight-bearing activities. The treating physiotherapist can advise which exercises are most appropriate for the patient and when they should be commenced.

For those patients who wish to return to running or sport, a graduated return to running program is required in the final stages of rehabilitation to recondition the LCL for running in a safe and effective manner. This should include the implementation of progressive acceleration/deceleration and change-of-direction running drills before returning to sport.

Prognosis of a LCL tear

With appropriate management, most patients with a minor to moderate LCL tear (grades 1 and 2) can return to sport or normal activity within 2 – 8 weeks. Patients with a complete rupture of the LCL will require a longer period of rehabilitation to gain optimum function. Patients who also have damage to other structures of the knee such as the meniscus or cruciate ligaments are likely to have an extended rehabilitation period.

Physiotherapy for a LCL tear

Physiotherapy for patients with this condition is vital to hasten the healing process, ensure an optimal outcome and reduce the likelihood of future recurrence. Treatment may comprise:

- soft tissue massage

- joint mobilization

- the use of crutches

- knee taping

- knee bracing

- ice or heat treatment

- electrotherapy (e.g. ultrasound)

- anti-inflammatory advice

- exercises to improve flexibility, strength and balance

- hydrotherapy

- education

- activity modification advice

- biomechanical correction

- a gradual return to activity program

Other intervention for a LCL tear

Despite appropriate physiotherapy management, a small percentage of patients with this condition do not improve adequately. When this occurs the treating physiotherapist or doctor can advise on the best course of management. This may involve further investigation such as an X-ray, CT scan or MRI, or a review by a specialist who can advise on any procedures that may be appropriate to improve the condition. Surgical reconstruction of the LCL may be required in rare cases of a complete LCL rupture when conservative measures fail.

Exercises for a LCL tear

The following exercises are commonly prescribed to patients with a LCL tear. You should discuss the suitability of these exercises with your physiotherapist prior to beginning them. Generally, they should be performed 3 times daily and only provided they do not cause or increase symptoms.

Your physiotherapist can advise when it is appropriate to begin the initial exercises and eventually progress to the intermediate and advanced exercises. As a general rule, addition of exercises should take place provided there is no increase in symptoms.

Initial Exercises

Knee Bend to Straighten

Bend and straighten your knee as far as possible and comfortable without increasing your pain (figure 3). Repeat 10 – 20 times provided there is no increase in symptoms.

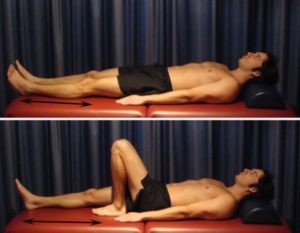

Static Quadriceps Contraction

Tighten the muscle at the front of your thigh (quadriceps) by pushing your knee down into a towel (figure 4). Put your fingers on your inner quadriceps to feel the muscle tighten during contraction. Hold for 5 seconds and repeat 10 times as hard as possible without increasing your symptoms.

Intermediate Exercises

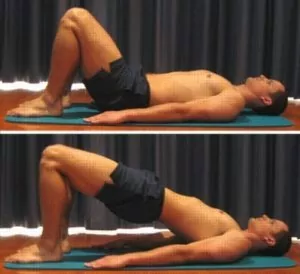

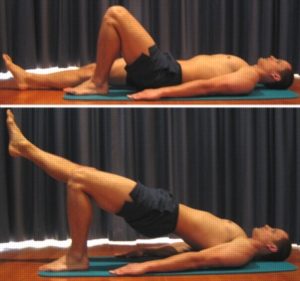

Bridging

Begin this exercise lying on your back in the position demonstrated (figure 5). Slowly lift your bottom pushing through your feet, until your knees, hips and shoulders are in a straight line. Tighten your bottom muscles (gluteals) as you do this. Hold for 2 seconds then slowly lower your bottom back down. Repeat 10 times provided the exercise is pain free.

Squat with Swiss Ball

Begin this exercise in standing with your feet shoulder width apart, your feet facing forwards and a Swiss ball placed between a wall and your lower back (figure 6). Slowly perform a squat, keeping your back straight. Your knees should be in line with your middle toes and should not move forward past your toes. Begin with a shallow quarter squat and repeat 10 – 20 times provided there is no increase in symptoms. Gradually increase the squat depth over a number of days so that eventually you are performing a squat to a 90 degree knee bend, provided there is no increase in symptoms.

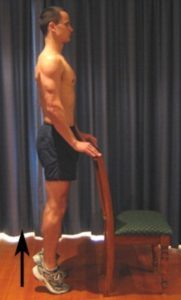

Heel Raises

Begin this exercise standing at a bench or chair for balance (figure 7). Keep your feet shoulder width apart and facing forwards. Slowly move up onto your toes, raising your heels as far as possible and comfortable without pain. Perform 10 – 20 repetitions provided the exercise is pain free.

Hamstring Stretch

Place your foot on a step or chair. Keep your knee and back straight, lean forward at your hips until you feel a stretch in the back of your thigh / knee (figure 8). Hold for 15 seconds and repeat 4 times at a mild to moderate stretch provided the exercise is pain free.

Calf Stretch

With your hands against the wall, place your leg to be stretched behind you as demonstrated (figure 9). Keep your heel down, knee straight and feet pointing forwards. Gently lunge forwards until you feel a stretch in the back of your calf / knee. Hold for 15 seconds and repeat 4 times at a mild to moderate stretch provided the exercise is pain free.

Advanced Exercises

Single Leg Bridging

Begin this exercise lying on your back in the position demonstrated (figure 10). Slowly lift your bottom pushing through your foot, until your knee, hip and shoulder are in a straight line. Tighten your bottom muscles (gluteals) as you do this and hold for 2 seconds. Then slowly lower back down. Perform 10 – 20 repetitions provided the exercise is pain free.

Single Leg Squat with Swiss Ball

Begin this exercise standing on one leg with your foot facing forwards and a Swiss ball placed between a wall and your lower back (figure 11). Slowly perform a squat, keeping your back straight. Your knee should not bend beyond right angles and should be in line with your middle toe. Your knee also should not move forward past your toes. Begin with a shallow quarter squat and repeat 10 – 20 times provided there is no increase in symptoms. Gradually increase the squat depth over a number of days so that eventually you are performing a squat to a 90 degree knee bend, provided there is no increase in symptoms.

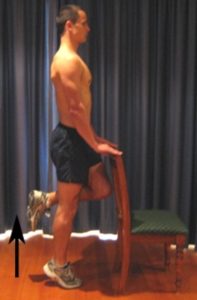

Single Leg Heel Raises

Begin this exercise standing on one leg at a bench or chair for balance (figure 12). Keeping your foot facing forwards, slowly move up onto your toes, raising your heel as far as possible and comfortable without pain. Perform 10 – 30 repetitions provided the exercise is pain free.

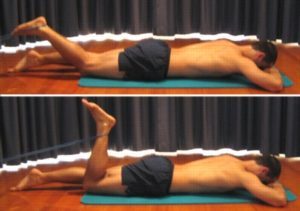

Resistance Band Hamstring Curl

Begin this exercise lying on your stomach with a resistance band tied around your ankle as shown (figure 13). Slowly bend your knee tightening the back of your thigh (hamstrings). Perform 10 – 20 repetitions provided the exercise is pain free.

Quadriceps Stretch

Use a chair or table for balance. Take your heel towards your bottom, keeping your knees together and your back straight until you feel a stretch in the front of your thigh or as far as you can go without pain (figure 14). Hold for 15 seconds and repeat 4 times at a mild to moderate stretch provided there is no increase in symptoms.

Rehabilitation Protocol for a LCL tear

The following is a general rehabilitation protocol for a LCL tear. This needs to be tailored to each individual and should be discussed with your treating physiotherapist prior to commencing. Progression through this program can vary from several days to many weeks depending on injury severity and quality of treatment:

- See your physiotherapist as soon as possible to confirm diagnosis, establish the likely prognosis, identify the contributing factors to injury and begin appropriate treatment.

- Follow the R.I.C.E. Regime for the first 48 – 72 hours. This should primarily comprise:

- Rest from any activity that increases pain (if walking is painful or causing a limp, the use of crutches and / or an appropriate knee brace are usually required)

- Ice the sore area for 20 minutes and repeat every 2 hours

- Compress the injured area with an appropriate compression bandage (this should be removed during sleep and loosened or removed if too tight).

- Elevate the affected leg above the level of your heart whenever lying down and as much as possible.

- Anti-inflammatory medication may be beneficial (discuss this with your doctor and/or pharmacist)

- Avoid H.A.R.M. during the first 48 – 72 hours following injury or when inflammatory signs are present (night-time pain, morning ache / stiffness or pain at rest) including:

- Heat (avoid using heat on the injured knee, this includes the use of heat packs, hot paths or spas)

- Alcohol consumption

- Rigorous Exercises of the affected body part (e.g. running / riding etc.)

- Massage

- The use of crutches is normally indicated if walking is painful or causing a limp. If using crutches, walk normally, but take enough weight off the injured leg so walking is pain free and limp free. Sometimes smaller steps may be required for a period of time. Gradually increase weight through the injured side as tolerated, over a number of days, provided there is no increase in pain or limp. Eventually progress to the use of one crutch (using the crutch in the opposite arm to the injured side i.e. right arm for left knee injury) and eventually no crutches (see How to Use Crutches).

- Aim for pain free rehabilitation (i.e. gradually increase strength, flexibility and activity, provided there is no increase in symptoms during activity or upon rest following activity. This should take place over days to weeks).

- Begin “Initial Exercises” 72 hours following injury provided there is no increase in symptoms.

- Heat treatment can usually commence after the initial 72 hours following injury provided there is no inflammation (i.e. night-time pain, morning ache/stiffness or pain at rest). Apply a heat pack to the injured area at a comfortable warmth for 20 – 30 minutes before exercises. If inflammation is still present (i.e. night-time pain, morning ache / stiffness or pain at rest) continue to use ice instead of heat.

- Increase walking distance, and eventually speed, gradually, and, provided there is no increase in pain or limp (this should take place over days to weeks).

- Progress to the “Intermediate Exercises” once the “Initial Exercises” can be performed pain free and to the same extent on the injured side as the non-injured side. Ensure all new exercises do not increase symptoms. The ‘Intermediate Exercises’ should be added to the ‘Initial Exercises’. Generally you should begin with one or two ‘Intermediate Exercises’ and then gradually add the remaining ‘Intermediate Exercises’ over a period of days to weeks provided there is no increase in symptoms.

- Progress to the “Advanced Exercises” once the “Intermediate Exercises” become too easy and can be performed pain free and to the same extent on the injured side as the non-injured side. Ensure all new exercises do not increase symptoms. The ‘Advanced Exercises’ should be added to the ‘Intermediate Exercises’ and should replace the ‘Initial Exercises’. Generally you should begin with one or two ‘Advanced Exercises’ and then gradually add the remaining ‘Advanced Exercises’ over a period of days to weeks provided there is no increase in symptoms.

- A gradual Return to Running Program should be implemented for individuals who aim to return to running following injury provided there is no increase in symptoms. This should include the implementation of acceleration / deceleration drills and agility running drills before returning to sport (see Return to Sport).

- A gradual Return to Sport and activity can occur provided there is no increase in symptoms. The use of an appropriate knee brace or knee taping techniques may be advisable when returning to sport, to minimise the likelihood of injury reoccurrence.

- Ensure your physiotherapist has identified the contributing factors to your injury and appropriate intervention has taken place to address these issues to minimize the likelihood of injury recurrence.

Physiotherapy products for a LCL tear

Some of the most commonly recommended products by physiotherapists to hasten healing and speed recovery in patients with a LCL tear include:

To purchase physiotherapy products for a LCL tear click on one of the above links or visit the PhysioAdvisor Shop

Find a Physio for a LCL tear

Find a physiotherapist in your local area to treat a LCL tear.

More Information

More Information

- View more Knee Strengthening Exercises.

- View more Knee Stretches.

- View Balance Exercises.

- View detailed information on initial injury management and the R.I.C.E. Regime.

- View detailed information on How to use Crutches.

- View detailed information on when to use Ice or Heat.

- View detailed information on a Return to Running Program.

- View detailed information on how to safely Return to Sport.

- View detailed information on Knee Taping.

- Unsure of your most likely diagnosis? View our Knee Diagnosis Guide.

Become a PhysioAdvisor Member

-

Individual Membership (12 Months)$59.95 for 1 year

Individual Membership (12 Months)$59.95 for 1 year -

Individual Membership (3 Months)$39.95 for 3 months

Individual Membership (3 Months)$39.95 for 3 months -

Individual Membership (Yearly)$49.95 / year

Individual Membership (Yearly)$49.95 / year -

Individual Membership (Monthly)$15.95 / month

Individual Membership (Monthly)$15.95 / month

Link to this Page

If you would like to link to this article on your website, simply copy the code below and add it to your page:

<a href="https://physioadvisor.com.au/injuries/knee/lcl-tear-members-only”>LCL Tear (Members Only) – PhysioAdvisor.com</a><br/>PhysioAdvisor offers detailed physiotherapy information on a LCL tear and LCL injury including: causes, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, exercises, rehabilitation protocol, physiotherapy products and more...

Return to the top of LCL Tear (Members Only).